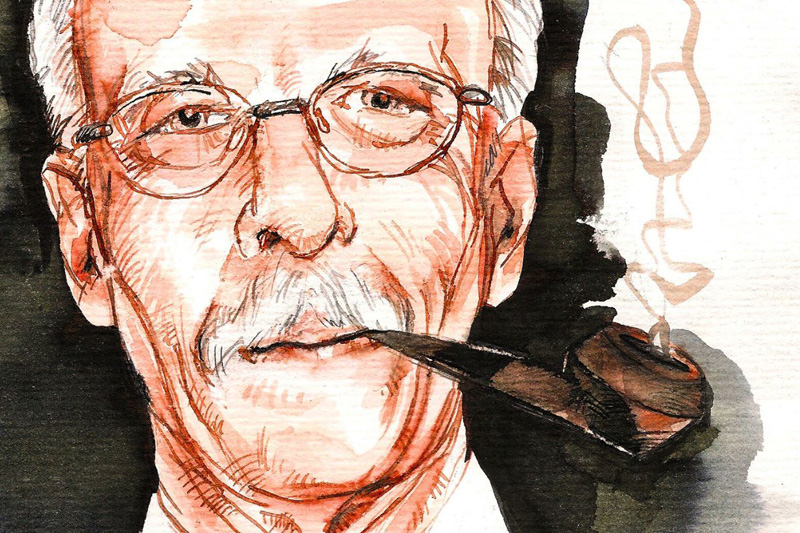

All Pipes Considered with Alex Florov

I recently had the opportunity to chat with artisan pipe maker, Alex Florov, about his experience creating high-quality, artistically complex pieces and his inspirations. Join in this engaging conversation about his passion and dedication to crafting pipes, utilizing natural materials wherever possible and taking immense pride and enjoyment in pipe making.

Note: The following transcription has been edited for clarity and brevity.

[Sykes Wilford]: Welcome to another episode of "All Pipes Considered." I'm Sykes Wilford, and I'm here with my good friend Alex Florov. Alex is a famous pipe maker. This year is his 20th anniversary of pipe making, and he is back here for APC for the first time in at least a decade. I'd like to welcome him to APC for the first time in many years. You did this once before with us, right?

[Alex Florov]: Yeah, about 10, maybe 15 years ago.

[SW]: It was a long time ago. So we have a lovely selection of your pipes in front of us, and I wanted to talk a little bit with you about your aesthetic influences. Especially in your early days, who were you looking to, and how were you looking at the pipe world? Because the pipe world was very different in 2004 when you started making pipes.

[AF]: Yes. When I started making pipes, I started on my own. I was challenged by my father-in-law, so I just made a few pipes out of the blue. I did some research and used a pipe kit. I didn't know how to drill. A big discovery for me was the Chicago Pipe Collectors Club, and a lot of wonderful people who were there helped me with the connections. They introduced me to famous pipe makers. I met you in 2005 during my first Chicago show.

That was a blast at the show. The Danish school was as pure as it could be. And when I visited your exhibition, I was absolutely astounded by Japanese pipe makers. The way they styled their pipes and incorporated grain into them was mind-blowing. Before that I thought that pipes could only be symmetrical, but Japanese people can do anything and keep the engineering intact. That's the most important aspect of the craft for me — it doesn't matter what the pipe looks like. If it doesn't smoke well, it's not a good pipe. Tokutomi in particular is more liberal with his creations in the Japanese market.

Alex Florov's Influences

[SW]: So Tokutomi was a major early influence for you.

[AF]: He was a major influence and is still a major influence on me. And even now I'd like to go back to 2006, 2007 Toku pipes and get some inspiration for what I could do applying today's skills and today's style to those shapes. Several of the pipes are a combination between the traditional Danish school and the Japanese school, like this pipe for example. The idea is a large Lars Ivarsson side-lined pipe, but I added a little bit more air to it because the hole was a part of the design, and kept a little bit more rough plateau on the bottom than most people do. That was just fun. You know, it's not like a regular job. It's fun. I talk to the wood, and the wood talks back to me. It's a very interesting process. Tokutomi reinvented the Cavalier, in my opinion: his Katana; I believe Thomas Looker named that one. It's an absolutely gorgeous Cavalier. It's so elegant, so thin, and it still sits. That's an amazing skill on top of everything else. And of course, I do a lot of bamboo work. When it comes to bamboo work, the first name that comes to mind is Smio Satou. He was the master of bamboo.

My designs are often influenced by a few guys, plus a little bit of my own thing. Bamboo pipes are kind of funny. You either find a bamboo piece first and try to fit something into it, or you start on the briar side, and then you spend weeks just to find the correct piece of bamboo to fit the particular briar. So it's a little bit more complicated than normal pipe design. But still, working with natural materials, that's what drives me on.

People who follow my pipes know I almost never use any metals. I recently started to use a little bit of titanium, because a friend of mine brought me some titanium. Metal can be fun, I'm not saying anything against silver or sometimes gold on the pipe, but it's not the materials that inspire me. I like all-natural materials, so bamboo is perfect for that because there are no two pieces of bamboo that are the same. It's the same as a block of briar. So every bamboo pipe is unique.

Briar pipes are unique too, because sometimes I'm taking blocks that have perfect regular grain on all sides. I'm like, "Oh yes, I'm going to do some straight grain," and I open it up and it turns into a Fugu Fish because that's the only way I can use those grains, because they go wild inside. This tail pipe is probably a good example of it, because from the top without the tail it looks like a regular, but the tail goes absolutely wild.

[SW]: Yeah, the angle of the grain is moving a lot as the block changes.

[AF]: Yes, so I knew I needed to keep the tail on. Thank God I didn't cut it on the disc too fast, because sometimes it happens and then I beat my hands, head, and everything else for not utilizing the whole thing, because my philosophy is one block, one pipe. If it's a large block, it's going to be a large pipe. But I need to keep all the natural flow in the pipes, the shape, and the grains. If there are some sand pits, I can either get around, change the shape, or I can do a combination finish and blast part of the pipe and leave the other side smooth, but keep it natural in the same way it grows on a tree. I just count to three and I pick the pipe like a natural fruit. It's not something that can be forced.

[SW]: I would like a tree that grows pipes.

[AF]: You know, I'd like to grow that tree too. Maybe one day I should plant pipe seeds in the pot and see what happens, you know? Maybe it will grow. Pipes for me are a way of life. I'm living in that world.

Pipe-Making Beginnings

[SW]: Were you a pipe smoker before you started making pipes?

[AF]: I was an amateur pipe smoker when I was about 18-20 after my military service. Then I stopped smoking pipes when I came to the U.S. because I couldn't afford most pipes, and for some reason, I did like Dunhill at that time. Later on, when my father-in-law challenged me, and then the appearance of the internet, there was a little bit more information about what kind of pipes were available. My attention was switched to Italian pipes, because they do pay a lot of attention to grains versus the shape. Slowly I got into the Danish style, which probably everybody comes through at that stage because you cannot pass Danish pipes while getting into the craft. Pipes and Denmark are intertwined as one for me. And then, as I said, I discovered the Tokutomi and Gotoh pipes and the funny thing is that I didn't understand the Gotoh pipes at first because they're more complicated. They look more simple, but they're way more complicated in style, so it took me a while to figure out why he was doing them that way. It's less playful, but it's more meaningful, I should say.

[SW]: When I think back to your very early work, and please correct me if you think I'm wrong, I remember seeing even a lot of Danish style then, but there was a more sort of baroque approach to the aesthetic. There was more detail work and there were different materials utilized.

[AF]: Yes.

Pipe-Making Motivations

[SW]: You're a Russian-American pipe maker. Were you reaching for other aesthetic things in Russian art, or where were those early designs coming from? And I still see it in your pipes a bit, but it's so much more subtle now than it was twenty years ago.

[AF]: My background is in wood carving and antique furniture restoration. Yeah, the baroque style is the right assessment, and that's probably where it came from. I worked with a lot of furniture, which was very intricately carved, and with a lot of different materials.

They implement amber, some minerals, and metals, and they build a harmony between those materials. And I think my initial driver was to utilize my wood carving skills, because I'm still using the wood carving chisels on the briar despite its really hard material. It's just easier that way for me. And I fell in love with briar right away. It's absolutely amazing wood that I cannot compare to anything else I know. And also, yes, I do like to use some exotic woods on my pipes as well to represent the natural beauty of it and to basically accent the major pieces of particular pipes.

When I began making pipes, I was crazy about colorful mouthpieces and acrylics. Probably a lot of pipe makers went through that phase. I determined, in time, that black is the best. I very rarely use traditional Cumberland, like Dunhill-style Cumberland.

[SW]: This one right here. That's beautiful with the stain color and then the Cumberland stem.

[AF]: This is a pure Toku influence. I have a similar pipe made by Toku, and it does have a Cumberland on it. So for me, that shape and the Cumberland went together. If the grain is good enough, and I can use that color, yes, it will pair with a Cumberland. If the color is different, and the briar sometimes comes in a darker shade as it is, where I cannot use that color on it, then it'll be a black stem. Black is the best color, just like Henry Ford stated. I will paint it any color as long as it's black. Yeah, so that's what I like. And I do like ivory right now. It's not very popular because of the whole tussle and bustle. I use a very high-quality imitation, like on this pipe, that's imitation ivory. And I think it just harmonizes the whole thing. It's not just creating the band between, it's harmonizing the major portion and the mouthpiece. For me, the pipe is a whole creation. I don't separate stummel, mouthpiece, or decorations.

[SW]: It's a complete composition.

[AF]: Yes, it's a complete composition. When I draw sketches, it's always the whole thing. That also helps give me an idea of the proportions as well. A drawing is like a guide. It's a very wavy guide, and when I sit at the disc, the design changes a lot. The size and the design. I just keep the proportions because that's what sketches are good for, to find the correct proportions for all the elements. Sometimes if I don't do that, it solely goes off of inspiration. I find the block, I see the pipe within it, and I jump to the disc and begin making it.

And then I end up with the question, "What kind of mouthpiece should this pipe have?" And sometimes it takes weeks to just figure that out, so I put it aside.[SW]: I've seen that in your workshop, where you've got a bunch of things you haven't quite figured out yet waiting at the same time.

[AF]: Yes, for example, this stummel was on my workbench for about three or four months. It was right after the Chicago show.

[SW]: So you made the bowl, and then you found the bamboo later.

[AF]: Yes.

[SW]: That's brilliant. It is a perfect, complete composition. It's like you designed the bowl around the bamboo. That's fantastic.

[AF]: Yeah, and that one has maple on it, almost looking like pearls or dots.

[SW]: It's beautiful. Let me ask you a bit of a trick question.

[AF]: Okay.

[SW]: Do you see this pipe as being influenced by Tokutomi or influenced by Jorn Micke? When you're making this pipe, are you thinking Tokutomi or are you thinking Jorn Micke?

[AF]: That is a really tricky question. First, you mentioned the name I respect a lot. For some reason, I didn't mention him earlier. The Jorn Micke designs, if you look deep into them, were the template for a lot of modern shapes we see around. And a lot of Tokutomi's aesthetic is loosely based on the Micke design. Not many people, especially the younger pipe makers, pay attention to that. But the reversed taper shank, that's a contribution of both. It's Lars and Jorn Micke.

[SW]: But then this bowl shape is very Jorn Micke, yet the design is more like something Tokutomi would do.

[AF]: Yeah. That would be what Toku would do to the Jorn Micke shape. And when it comes to the Fugu Fish, it's still hugely controversial who the first was to separate the grains.

[SW]: Oh yeah, that is dangerous ... There's a minefield. I have no opinion.

[AF]: Me too. I have friends on both sides, so I wouldn't elaborate on that point. I do have friends on both sides, and I am lucky to have a lot of friends who collect Jorn Micke and old Lars and really old Danish pipes from the '50s and '60s. I'm always digging into the treasure chest and looking to see, "There's that line, I used that line. That must be old." It's kind of like traveling backward in history.

[SW]: And it's additive too. You can peel back each layer of an onion, one step at a time.

[AF]: Yes, absolutely. Pipe brand catalogs are a treasure.

[SW]: Oh yes. The pipe brand catalogs are fantastic. And so you're sort of working your way forward through this, and at no iteration is it fully new, but by the time it's gone through four or five or six layers of that onion, it's very different aesthetically.

[AF]: Absolutely. I really like looking at the history of pipes. It shows the development of shapes, how to incorporate grains in different ways, how to use extensions and decorations, and even the connection point. Some pipes look way better with this traditional push-in connection. Some pipes literally require the military mount because the end of the shank needs to remain open for the smoker. That's what the smoker sees when he smokes. So it's always a balance between shape, engineering, grains, finish, and a mouthpiece of course. The mouthpiece is one of the most important elements because it connects the smoker to the pipe. There's always a challenge in pipe making, and I like to challenge myself.

If I drew some crazy sketch, I would kick myself and say, "Hey, can you do that?" So if I find the right block, yeah, I usually jump on it. Sometimes it takes longer. Sometimes I have a very complicated pipe which I completed in less than, I don't know, 30-40 hours because I was doing one particular pipe nonstop. I was not juggling different pieces as I usually do, because I liked it so much and wanted to see it finished. This pipe, for example, was a challenge by the grain itself, because that side is almost perfect straight grain. I knew it wouldn't have perfect grain, but it looks so cool, so I'm trying to save it. And the other side is basically pure birds-eye on a Volcano.

[SW]: I think that shape is a good example of an interesting mashup of different styles. This is quintessentially you at this point. But I see a little bit of Satou going on in there, and then I see a little bit of Tokutomi going on in there, and some Danish influence all rolled into one pipe. And that's not to take anything away from what you're bringing to it as a pipe maker aesthetically, but it's neat seeing something uniquely yours and also quite novel, that you can also lay in this matrix of other pipe-aesthetic movements and other styles. It's really a cool pipe.

[AF]: Thank you. It's immensely fun for me. Even sanding can be exciting, though it is mostly boring moving from grit to grit, but the initial sanding allows you to see the grains with a better view for the first time. The last sanding is fun too because the stain is already there, so I can see the grains in a whole new beautiful light. For me, the most beautiful process is oiling. That's the best. That's when you see the grains pop up.

As for the drying process, it's kind of boring because I'm not doing anything for the pipe for a week or so. But yeah, as I said, it's just so much fun just to make a pipe. I think that's most of my motivation in pipe making, taking a block and turning it into something beautiful.

[SW]: That's a good motivation.

[AF]: The hardest part sometimes is parting with the pipe when it is complete and ready to go. I spend quite a lot of time with that particular piece, and I fall in love with it, and then all of a sudden I have to give it away. But I do have my collectors, and I like them all. And when I see somebody smoking my pipe, it's like the best compliment I can get. I'm looking at one of my pieces that you're smoking now.

[SW]: It's the first time you've seen it in a few years, huh?

[AF]: Yeah, that one is from a long time ago.

[SW]: It says 2014 on there.

[AF]: I thought it was older, maybe 2006 or 2007. But you know, it has Japanese bamboo that somebody gave me from the Tsuge factory.

[SW]: That's a beautiful pipe.

[AF]: Thank you very much. As long as you enjoy it, that's all that counts.

[SW]: And I've been enjoying it for 10 years now.

Shape, Engineering, and Proportions

[AF]: Cool. See for me, there are three important things: shape, engineering, and overall proportions.

[SW]: And engineering is not a small feat when you're talking about a shape like this. Trying to make sure that this functions well as a pipe is not a small project. Do you want to speak to the challenges? It's very easy to correctly engineer the inside of a Billiard, but it's a rather different story in one that isn't as conventional of a shape.

[AF]: Well, inside the Cavalier, I wouldn't say it's cheating, but there is a little bit of relief because it's drilled all the way through. So my connection point for the draft hole technically can be anywhere, according to the height of the pipe. The challenge is actually fitting the draft hole somewhere so it's not coming out. So when this particular pipe was drilled in three different planes, I set it up three times on my machine to drill it all. And I used an angled plate and a dividing head on it. I mean, all tricks for the machinist. My second background is as a machinist, so I prefer heavy machinery. Even now I do.

I totally admire Japanese and Danish pipe makers who do it all by hand against the rotating tool. In my opinion, it's a little too dangerous. And I'm nuts about precision. You saw my machine, it has all digital readouts in ten-thousandths of an inch.

[SW]: Yeah, I can't deal with that level of precision.

[AF]: Precision is very important, because if the pipe doesn't pass the cleaner, well, it's not a pipe. It's like brushing your teeth in the morning, something like that. Another thing, the engineering of the mouthpiece in particular, I'm totally nuts about it. If I can't execute it correctly, I wouldn't do it that way. I've had a few cases where my friends come to my shop, with whatever pipes they smoke, and I notice the mouthpiece is wrong in some way. So I tell them, "Can I make you a new one?" And it's actually worked. People claim it smokes better. I read about it in an article by Rainier Barbi. He was my inspiration for precision and engineering. And man, he was a great guy.

So it's not only like Danes or Japanese — pipe smokers and pipe makers are one big family. And what I like about that business, trade, craft, art, any word will fit; we're not competing against each other like in most of the industries. We're mostly complimenting each other. When we attend pipe shows and meet, we admire each other's work. We're not trying to brag. No, it's absolutely different. It's a family style. The same goes not only for smokers or makers, but for retailers as well, for people like you. I've known you for 20 years, and we've been friends for 20 years, and I'm totally honored because of that.

[SW]: Me too.

[AF]: Pipe shows aren't exactly a commercial enterprise. It's meeting with friends, spending time with them, and chatting. With the internet, selling is not as hard as it used to be. You just put your pipes on the internet, and people buy it. But a pipe show is still very important. It provides an opportunity and a space for us to all meet in one place, chat about our stories, pipe stories, and our life stories. We all have families. We all talk about our families. I mean, it's impossible to describe.

My first impression of my very first Chicago show, 2005, was that it's a different planet with totally different people. It's a bunch of aliens. It's great to see my friends and the friends who joined in the same year, growing and expanding their skills. I've expanded my skills. We compliment each other every time we see one another. That's why I'd like to stay in this business and do whatever I like and keep it that way.

I didn't say anything about tobacco yet. So I'm a pipe smoker. Well, I'm a Virginia smoker, pure Virginia. But sometimes something else too. I like Cornell & Diehl and some other companies too. Well, I just smoke one brand sometimes, but that's kind of off topic. And here's another thing which I actually want to mention. Speaking of Jorn Micke, that's my iteration of 1960s Jorn Micke.

[SW]: Yeah. That's beautiful.

[AF]: Very early Jorn Micke. The fun aspect of that pipe is that it's less sculpted and that it's more clay-sculpted. So the idea was to make it look like it's soft, somehow sculpt it, and then make it hard. The grains actually cooperated.

When it comes to pipes, some people say I'm kind of an extremist because some of my pipes are really thin-shanked, with really fine proportions, yet some are really large and bulky. I like both worlds, small pipes, and large pipes. I know some people do only large pipes, and it's actually fun on its own. I made a few Magnums in my days, and it's just a different experience. I like it. But again, people are all different, and obviously, they require different pipes.

[SW]: You have so much skill as a craftsman, so it gives you tremendous flexibility in what you can do.

[AF]: It gives me flexibility, but I'm still keeping it in that style. I do make classics once in a while, and there are a few reasons for that. Reason number one, sometimes I just get challenged. There was one case when I made a straight Billiard entirely on a sanding disc, no lace. Just to do it. That was fun.

[SW]: Also, straight Billiards are not easy shapes to make. It's very hard to get it right.

[AF]: Yes, that was an in-passing challenge by Former. That's a famous Former quote: "If you cannot make a straight Billiard, you're not a pipe maker." And some of my friends passed me that quote, and they actually brought Former to my table. And the next year I came, the first thing I did was take that Billiard, go to Former, and said, "Look," and he just laughed. He totally understood why I made it. But I like classic shapes. The beauty is in the simplicity, and it's really hard to make it beautiful and simple at the same time.

[SW]: Yes. It has to be exactly right to make a classic shape perfectly by hand.

[AF]: But I like the challenge too. I like to expand and utilize all my skills. I enjoy expressing myself completely, and showing everything I can do. I'm totally into Japanese and Chinese design, art, and style. Their view of the world is in images. They put soul in everything. For example, a stone on the side of the road, it has a soul. There is a tree over there, that has a soul too. So when I make a pipe, I think I put a little bit of myself into it. And when I smoke pipes made by my friends, I actually can feel it. I call it sentimental smoking. I own a lot of Peter Heeschen pipes. And for me, when I'm smoking his pipes, it's like I'm sitting right next to him and remembering Uncle Peter.

[SW]: Of course.

[AF]: Pipes are not just a utility instrument, that's only the first purpose of it. As one famous pipe maker once said, it's a functional art. So it's a piece of art that can be used for something else, less than a display. And I know some of my pipes I made a long time ago, they haven't been smoked yet. I've seen pictures of them. Well, all of my pipes are intended to be smoked. That's why I always keep engineering in perfect condition, with the finishes and briar carefully chosen and completed.

Luckily, I do have friends like Mimmo who supply me with really good briar. I season them for at least five to seven years. In my opinion, it does add a little bit to the taste, but what it does the most is it makes the grain stay out better. Because sometimes there is a flaw that you cannot see on a fresh block. Give it five to seven years, you realize there are sand pits here and there. For me, it's easier to avoid it just to see it. Some people say the seasoning is good for taste. Maybe. That's kind of a big question people still have no concrete answer to. My answer is that's how I can see all the flaws.

[SW]: That's interesting.

[AF]: I recently realized that. Around 15 years ago, I started to season my briar when I had the ability to do that. Some flaws that arise aren't visible right away. Sometimes when a block is fresh, not all the grain is visible, and that's important too. Seeing flaws takes some time.

Future Pipe Making

[SW]: Let me ask you another question to wrap up here. Where are you headed for the next 20 years?

[AF]: I'm trying to keep the Freehand movement going, so I'll continue to do what I'm doing. As you mentioned, my designs have become a little bit more subtle and refined.

[SW]: I don't see a lack of playfulness in your more recent work, but I do see refinement in your recent work. But that's been true for a number of years now, like a decade.

[AF]: That's what I've been trying to do. Again, I mentioned Kei Gotoh. I'm kind of trying to switch to the direction he's moving in, to make fewer lines but still as beautiful as possible.

[SW]: I see what you're saying, sort of more minimalist than your present label.

[AF]: It's not because I'm getting lazy. It's actually much harder to do it this way, but I like to challenge myself. It also shows maturity through the evolution of the pipe, much like pipe smokers evolve. Most people start with Aromatic tobacco, a full bent pipe, playing Sherlock Holmes, and that type of stuff. And if they're still smoking pipes 10 years later, but now it's a straight Billiard and Virginia, yes? It's like a step-by-step evolution, I just omitted a few steps in between. I think with pipe making, it's a similar thing. I already mentioned the colored mouthpieces, everybody comes through that phase, and some people stay in that phase and there's nothing wrong with that. It's just the way they like their style. And we have so many collectors and smokers that the pipe will find an admirer.

For me, I'm trying to create beauty in the mystery. So you need to spend some time with the pipe, following the lines, and kind of understand the design to see what I've been thinking about it. I had really good teachers who taught me the philosophy of pipes. If there is a line, that line's supposed to be as long as possible so your eye travels continuously all over the pipe back and forth. So you see all the grains, the curves, all the rough plateaus versus the straight grains. I mean, in this case, there are totally opposite grains. I utilized the natural shape of the block as well. That's why on the front all the grains are in harmony.

[SW]: And it only works because you adjusted the shape to the block.

[AF]: Absolutely. It's not forced. It is a Jorn Micke influence on Tokutomi, and Tokutomi and Jorn Micke influence on me through all of those years. And that's basically one of my interpretations of Tokutomi Discus, which comes from the Jorn Micke design.

[SW]: And there's this enormous body of work that is always bubbling up.

[AF]: Yeah, and thinking of it, there's an enormous amount of years of development for the particular shape. It's not one pipe maker who developed it on their own. It started in the late '50s, and early '60s, and it's continuous now, and I hope it will continue years and years after me. It's just something we like to play with. I come back to some of my older designs and I refine them, and it looks like a completely different pipe.

Especially now, we do have a lot of different bamboo supplies. I know I have about five or six different species of bamboo in my disposal, and they all require a different approach. So that is a challenge in itself. A lot of bamboo is already curved, so it's drilled in the curve. I didn't bend it after all, so it's a lot of different techniques as well. So it used to be just straight bamboo, which was a breeze to drill. No problem. Now everybody is using the curved one.

There is always something new and different in pipe making. Thank God right now we have a wider amount of tools. Twenty years ago, for example, it was really hard to find a chamber drill. Now I own probably 30 different chamber drills for all kinds of chambers, based on their size, shape, and anything else. And I just recently realized, I've been looking at old Tokutomi bamboo Dublins, and he had a pointed chamber there.

[SW]: Oh yeah, they were. I think that, in some respects, might have been a limitation of tooling. I don't know. But they're very short.

[AF]: Well, there was a limitation of shapes you could use. Nothing except a straight point could be used because of the outside shape of the pipe, but you could raise the bowl up a bit and give yourself a little bit more space if you needed to. Dublin is always a challenging thing actually because of the thin bottom.

[SW]: Yeah, that's true.

[AF]: But I was looking recently at the four and the five. They were extreme. I just recently looked at them, like, "Yeah, I remember." I held those pipes in my hands. I put my finger inside, and actually, I knew they had a straight taper. I placed an order for a few new tools. So I have 30. It is going to be more than 30. And you know, having more tools for me means I can make more stuff. I can broaden my mind, and, well, I'm fine with that.

[SW]: Alex, thank you so much for coming today and joining us in the studio to talk about your pipes. This has been so much fun. And check out Alex Florov's pipes on Smokingpipes.

[AF]: Yeah, thank you very much. I'll be honored.

Comments